The only way to really do justice to this film is to project it on a screen the height of Everest, to really revel in its wonder and the impossible temptation to scale its heights.

From the opening purple-tinted vision of Everest this film lives up to its title: It is a true epic that overshadows the modern trend for equating ponderous length and bloated budgets with grandness; even when shrunk down to cinema size this film remains an epic to cherish.

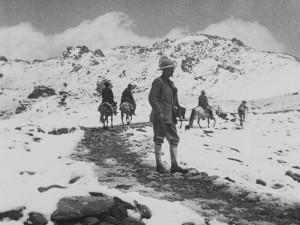

We follow a 500 strong group of men, women, and donkeys on their arduous journey that starts with the challenge to reach the foot of the highest peak in the world. As they climb higher the team gets smaller, the donkeys are replaced with yaks and Everest itself becomes an ever more imposing presence. Chronicling the third attempt to climb Everest led by George Mallory this film was shot, directed, and produced by Captain John Noel. The Epic of Everest is more than an official record or mere travelogue but rather a paean to the eternal struggle between man and nature.

We follow a 500 strong group of men, women, and donkeys on their arduous journey that starts with the challenge to reach the foot of the highest peak in the world. As they climb higher the team gets smaller, the donkeys are replaced with yaks and Everest itself becomes an ever more imposing presence. Chronicling the third attempt to climb Everest led by George Mallory this film was shot, directed, and produced by Captain John Noel. The Epic of Everest is more than an official record or mere travelogue but rather a paean to the eternal struggle between man and nature.

As well as beautifully restoring this 1924 film the BFI have commissioned a new score for its re-release. Simon Fisher Turner’s soundtrack brilliantly compliments this wondrous work. He somehow captures the daunting power of this towering peak and his propulsive rhythms add to our feeling of being a fellow traveller. Turner also incorporates found sounds and Nepalese instruments and vocals to give real texture to this remote world. And what a world, almost ninety years may have passed yet these images remain stunning. The camera never moves but Noel has a real eye for capturing the landscape. We get a sense of the wonder he must have felt and also the sheer size as we look upon explorers in their woolly jumpers and jackets dwarfed by vast cliffs of ice.

Noel’s intertitles give us an insight into the journey and his preoccupations. They give detail on the Tibetan tribes they encounter and the ancient mountain monasteries whose construction is a mystery even to the locals. But these are Imperialist times and Noel can be condescending about the local way of life and inhabitants who have no desire for greatness. However, he does respect the views of the native monks as they speak of the mountain they call ‘Goddess Mother of the World’. He also has genuine respect for the Sherpas (both men and women) that are normally the unsung heroes of mountaineering exploration.

Noel’s intertitles give us an insight into the journey and his preoccupations. They give detail on the Tibetan tribes they encounter and the ancient mountain monasteries whose construction is a mystery even to the locals. But these are Imperialist times and Noel can be condescending about the local way of life and inhabitants who have no desire for greatness. However, he does respect the views of the native monks as they speak of the mountain they call ‘Goddess Mother of the World’. He also has genuine respect for the Sherpas (both men and women) that are normally the unsung heroes of mountaineering exploration.

The colour tinting adds character when needed but Noel’s real achievement, in the harshest of conditions, is to capture step-by-step this strange journey. When sitting in a warm cinema this expedition can seem like some sort of madness but for John Noel there is no doubt: this is a noble cause and it is a duty for man to attempt to conquer nature. As Noel’s camera looks on (with his much-cherished telephoto lens) at distant ant-like figures in the vast snowscape we know there can only be one victor.

This review comes from a screening at the 57th BFI London Film Festival (LFF2013).

Follow Rob on Twitter @Rob_Munday

Follow Front Row Reviews @frontrowreviews