No one really knew what to make of Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess when it hit the festival circuit early last year. Mark Kermode came closest when he referred to it as a “mock-doc-cum-existential-comedy”. And if that sounds strange, wait until you actually watch the thing.

No one really knew what to make of Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess when it hit the festival circuit early last year. Mark Kermode came closest when he referred to it as a “mock-doc-cum-existential-comedy”. And if that sounds strange, wait until you actually watch the thing.

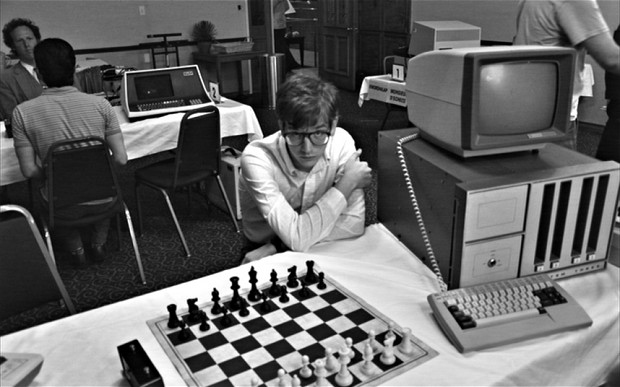

Computer Chess is a faux-documentation of a weekend-long computer chess tournament (that is: a tournament where programmers battle their chess-playing software against others’). Among these competitors are former title-holders Beuscher (Wiley Wiggins) and Bishton (Patrick Riester), their mentor Tom Schoesser, cocky maverick Michael Papageorge, and the first ever female competitor Shelly Flintic. Other characters include small time drug dealers John and Freddy, a wandering prostitute, and a group of couples on a ‘self-awareness’ course attempting a spiritual journey to enlightenment.

Over the course of the weekend there are technical setbacks to over-come and human tantrums to placate, a plague of cats to circumnavigate and religious experiences to be had – and near the end things take an even more bizarre turn.

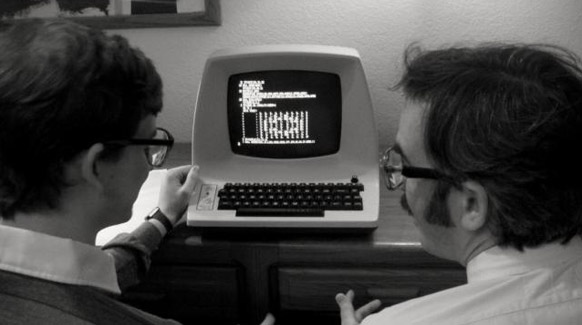

The most obviously note-worthy aspect of the movie is its aesthetic. The film was shot on black and white video using a Sony AVC3260 (and, for a brief and trippy sequence, in colour with a Bolex), the grainy quality of which perfectly evokes the period. There’s something about the varying shades of softly delineated grey that feels ancient and in its own way kind of sacred. There are also some wonderfully authentic outdated special effects: disorienting split screens, naff-looking explanatory text at the top of the screen, plenty of strobing. Make no mistake; this is a perfect marriage of content and form.

This, however, isn’t just arbitrary 1980s nostalgia. There’s nothing gratuitous about the period setting, it is rather a starting point for ideas (technological-cum-philosophical) and a heavily affecting atmosphere (the still-intense dregs of 80s anxiety that were felt towards the end of the cold war).

The narrative is strange and goes off in directions that you certainly wouldn’t expect. This is not a ‘sports movie’ in which the former champion faces various obstacles before reclaiming the title; in fact, the outcome of the tournament really doesn’t matter by the end. And what initially appears to be narrative about the introverted Bishton enjoying an awkward coming-of-age experience develops into a far more perplexing experience.

The narrative is only one of the film’s many fascinating aspects. The cast is also a marvellous little curio in itself, featuring among others: an unrecognisable Wiley Wiggins (whom people might remember from Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused and Waking Life), film critic Gerald Peary in a wonderful performance playing the Chess master, Austin animation guru Bob Sabiston, and real life software developer James Curry (I defy anyone to find an actor who could capture the identity and mannerisms of a software engineer better than Curry does here). The film boasts uniformly spot-on performances, adding further credence to Rosselini’s philosophy of non-professional casting.

One of the things that occurred to me, that I don’t think has been mentioned by any other critic, is the psychedelia of it all. Here, I not only refer to the narcotics that are discussed and consumed during the film, but also to the loose allusions to 2001: A Space Odyssey (even if it reduces the philosophical ideas to a synthesised hum) and the hallucinatory quality of the aesthetic, which is dream-like and hypnagogic. There’s a moment in which, over a drink at a bar, one programmer explains to another than not only are they certainly being watched by the government, but that there’s actually a totally valid reason for that (to explain any more would ruin the fun).

Of course, Bujalski, as the godfather of ‘mumblecore’, is a subtle film-maker – which means that all of this (the plague of cats, the labyrinthine hotel) is dealt with in an incredibly gentle and quiet manner. And this, in many ways, makes it all the more surreal.

Despite it all, however, Bujalski is so utterly affectionate towards characters that could easily be exploited for cheap laughs that what he’s created amounts to a series of touching meditations on loneliness, humanity, repression, and chaos. Bujalski has achieved that rare thing: a film that both creeps into the mind and under the skin, but also into the heart (just about).