This is the third consecutive volume of BOYS ON FILM that I’ve reviewed for this site and I always welcome the return of the wonderful series of collected gay short films. This, like the previous two installments, is a fantastically curated number of impressively accomplished little movies that, if not always great, always show a spark of great things to come from their directors or under-the-radar stars. I feel the only thing that’s missing from BOYS ON FILM 11 is a little bit of levity – a couple more in the vein of either It’s Not A Cowboy Movie from vol. 9, or A Stable For Disabled Horses or Yeah Kowalksi! from vol. 10.

The collections starts with an immediate high point: We Are Animals. Dominic Haxton’s fabulous film is set in 1985 (the literary significance of which is clear from the start) and depicts a dystopic world in which homosexuality is outlawed and dissidents are castrated. Though I was initially wary of the cheesy news-flash and the tasteless kitsch credits, the camp faux-sincerity quickly won me over. Despite the dark (and deliberately explicit) allegory, this film is wildly entertaining and occasionally very funny. There’s something liberating about the brutal horror mingling with exuberant moments; a ‘pink panther’ logo flashing up on screen in a batman-style interlude for example, or the hilariously well-timed appropriation of the slogan “we’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” I suppose it’s mainly just a pleasurable twist to see powerful gay militant rebels, rather than impotent gay victims – and despite this role reversal, the message isn’t lost.

This is followed by the exciting Burger, a tale of a post-night-out antics in a kebab shop. The overall production quality of the film is a little iffy (some of the performances aren’t great, others are just about on the mark), but it has been nicely written, shot, and cut, allowing drama to bubble just beneath the surface for almost the entirety of it’s running time. Thus, not only does the film’s aesthetic achieve exactly the right level of dirty realism, but the tone (which is exactly that of a slightly soured night-out) gives Burger a genuineness. The tension just builds and builds – beyond the the surface joviality everyone is giving off slightly bad vibes. The final moment will either leave a smile on your face or leave you rolling your eyes. Either way, that late night paranoid communication breakdown is evoked very nicely.

The collection’s first bum-note comes with Alaska is a Drag, which is a shame because the central idea behind the film is a nice one. Martin L. Washington Jr. plays Leo, a defiant drag queen who has been sent to an Alaskan fishing port by his dad in order to toughen him up. The fabulous protagonist who at first seems so out of place (his disco fantasies whilst as work are disrupted by fish guts being thrown in his face) is actually quite handy in a fight and this catches the eye of Spencer Broschard. The dialogue is full of sass: “Why did they fight you?” Leo is asked. “Um, let me see: I’m a fag and I live in Alaska…” The scene in which the two bond over a couple of drinks feels like exposition for a Rocky style film, but Shaz Bennet’s sweet little movie doesn’t really go anywhere and the little plot it does boast feels a little too predictable, even a little too dramatic. Aside from some sporadic humour, it mainly gets by on the charisma of it’s actors. Script aside however, Bennet could well be one to watch for.

The other weak film of the bunch is the Scandinavian Three Summers. Split into three parts (‘Last Summer’, ‘This Summer’, and ‘Next Summer’) the movie follows the exploits of a kid who befriends, falls for, and is betrayed by, a middle-aged family friend. It starts with such promise: ‘Last Summer’ depicts the two families meeting for lunch followed by a lovely little scene in which the young boy and the grown man go for a walk and bond over secrets. During this scene, the director really captures the lazy haze of a summer afternoon – the comfortable heat, the woozy lack of responsibility. In the film’s second act, it is revealed over another dinner scene that the pair have been emailing since ‘Last Summer’ and here the clandestine friendship feels genuine. The script shows a clear understanding of the texture of a conversation that only just hides sexual feelings. The problem is that each section is weaker than the last, in fact it kind of leaves one wishing the director had fleshed out the first act and turned that into the whole movie. At times the soundtrack is kind of distracting, and both visually and narratively Three Summers becomes more and more boring.

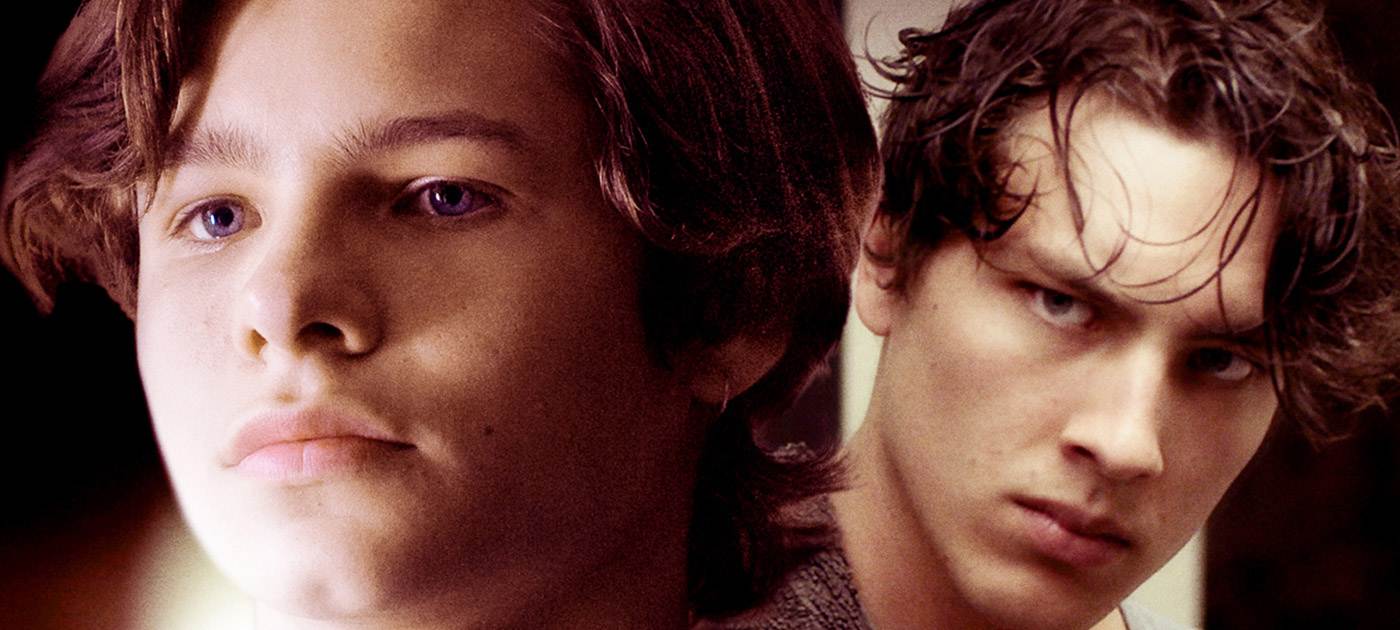

Luckily the following film is Nicholas Verso’s The Last Time I Saw Richard, an Australian teen horror/drama about depressive teens. Despite my feeling that the story is rushed (indeed, the film could certainly be adapted into a slow-burning feature length), Verso’s gothic movie creeps in all the right directions. Aesthetically it is superior to a most of the others in the collection and it finds the sweet spot between emotive drama and effective horror. On top of this, Verso manages to squeeze a nice little playful streak, some serious undertones and some very nice performances from a couple of talented young actors. The amount of ideas in this short shows that Verso should comfortably move towards making features.

Far more subtle, but in many way equally as creepy is Elder Rapaport’s Little Man, a strange and fairly enigmatic movie with some serious socio-political commentary. Daniel Boys plays an adorably shy guy who can’t seem to hold down a relationship. The film sneakily lulls you into a false sense of security (particularly with an early stoned conversation between he and his brother) – it’s not until a taxi ride back from a club that Rapaport’s (worthy) agenda becomes apparent and then things get weird (in a way that feels somewhat influenced by Shallow Grave). The film has been expertly cut together and has a gorgeous soundtrack, but naturally its most notable facet is that the way in which it cleverly addresses the stereotype of homosexual polyamory .

Perhaps the most accomplished of the bunch (or at least the most sophisticated) is For Dorian, a moving portrait of a Downs Syndrome boy’s relationship with his father. Though there’s not a huge amount of plot development in the film, suffice to say this is the most emotionally affecting of the bunch. It’s also the most beautiful to look at.

The best, however, was saved the best til last. Spooners is an absolutely wonderful film about a gay couple who decide they need a new mattress. This is perhaps the first film I’ve seen which acknowledges (and marvelously sends up) a new and commonly perpetrated homophobia involving a patronising over-compensatory acceptance of homosexuality followed by an uncalled-for fascination and an insistence on a number of ridiculous stereotypes (a sort of sexual equivalent of Orientalism). The film absolutely hits the right mark tonally, addressing hetero-normative prejudices in society, whilst simultaneously unleashing hilarity. This collection ends on exactly the right note; highly astute and the very meaning of levity.