Pieter-Jan De Pue’s fantasy documentary The Land of The Enlightened had it’s UK premiere in Sheffield Doc/Fest in 2016. Now available on DVD, Genevieve Bicknell looks back to that premiere and to the conversation with it’s director about time, responsibility, and negotiating with militias.

You created a work that slips between fiction and documentary, shot on 16mm film, in Afghanistan, in the midst of one of the world’s most dangerous conflicts. What made you decide to do this?

I felt very empty after film school. I didn’t feel ready to make a film. I was very young, I was 24 and I didn’t know what to make a film about. So I just said ‘ok I’m going to travel’.

Before going to film school, I worked as a photographer in the Middle East and South America, so after I graduated I thought that I would go to Afghanistan, to see the country and explore it as I had explored other parts of the world.

I knew that it was going to be very difficult to travel around as it was a war-torn country. Even though the Taliban had been removed from power, it was a very difficult situation. So I got in touch with several humanitarian organisations, and said ‘look I’m a photographer, I don’t have a lot of experience but maybe we can make a deal. I will take pictures for you if you give me access to your projects, guide me around and give me transportation and accommodation.’ I started working with 5 NGOs in 2007 and in 2008 I did the same thing but with a bit of payment. I got embedded with the American army, the Belgian army, the German army and some other NATO operations so I had a very clear idea of what the war in Afghanistan looked like.

The film moves between observational footage of the American army and a dreamlike world of stories and adventures led by children. How did you develop this more fantastical narrative?

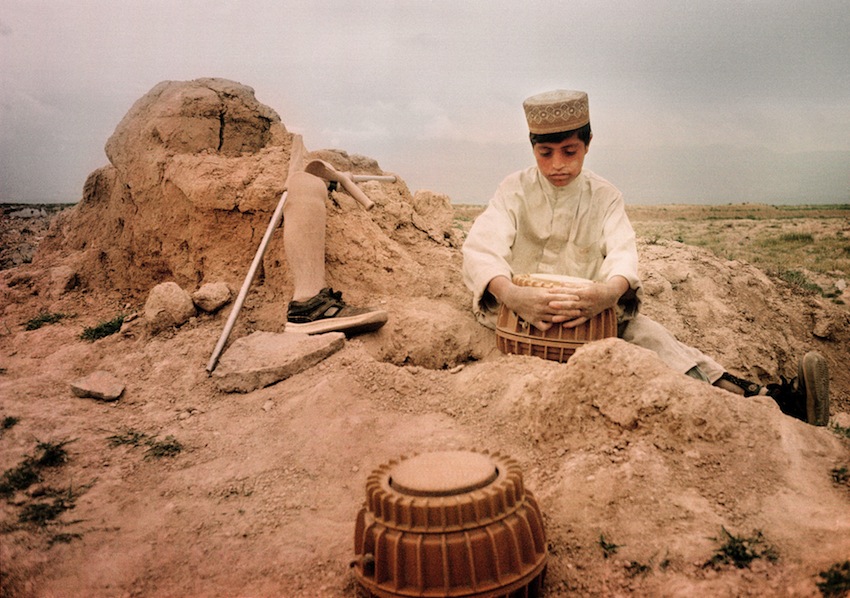

By working for the humanitarian organisations and by traveling around with some Afghan friends, by horse and on foot, I discovered that many kids were making an economy out of the war by selling scrap metal, looking for brass, selling explosives and working in the opium trade, and I thought that would be a very interesting topic. At the same time I discovered how many dreams those kids had. They were dreaming about what was going to happen to them after the withdrawal of the American troops. Kids were telling me fantasy stories like ‘when the Americans are going to leave my country, I’m going to be King and grab the palace and marry the most beautiful girl and have an army of my friends to protect me’, or ‘I’m going to take my horse and escape to the stars and leave the reality of Afghanistan behind’. And I thought it would be very interesting to show the world of Afghanistan seen through the eyes of these Afghan kids, diving into their imaginations and visualising their dreams. We knew that if we were going to do that it was going to be a very hybrid film as if you are going to visualise dreams you are moving into fiction.

The observational sections with the American army are very powerful. We are let into the worlds of the soldiers, and we get a sense of their dreams, through their conversations and the songs they create. Since this approach was so effective at showing us the dreams of the soldiers, why did you not use it with the children? Did you attempt to?

Yes, but there were several reasons why it didn’t work. With the American army, filming was very easy. Sometimes it was dangerous because we were in the middle of a conflict, but the army took care of us. They flew us everywhere, helicopters dropped our equipment wherever we needed it, they gave us food, protected us, and in 90% of cases, we were allowed to shoot everything that we wanted, so that’s why we were very close to the men. There were moments of boredom which were very interesting, as you see guys taking a guitar and improvising about their future and about what’s going to happen with the brass that the kids were making off with. It was very organic.

The problem with the kids was that we were alone in Afghanistan in tribal areas where the government of Kabul had no power, so we were relying on the local warlords, militias, and Taliban. We were attacked several times and had to rethink the whole approach. It ended up taking 8 years.

For each location, we needed to create a safe zone around us, so we needed to hire several people from those militias and we needed to negotiate with them for a long time. It was just impossible to stop at a village and meet kids and stay a week with them and film with them and try to go into their minds. They would have attacked us or we would have gotten kidnapped. I also needed to understand the culture of the kids and to talk their language so that took me a very long time.

When we found Gholam Nasir, I realised he was a very strong character and could be a voice for the kids. I decided to project all the fantasies that I had discovered, onto him. He is not an actor, so I couldn’t tell him ‘now you are going to walk to there’ for example. I wanted to capture him as I did the Americans, in a very natural way, but at the same time, I wanted to project my idea onto him. For example I projected the idea of the kid who wants to become the King of Afghanistan onto him, by saying ‘ok you want to become the King of Afghanistan, what are you going to do?’ And he told me ‘I’m going to gather my boys together, we are going to get our horses and Kalashnikovs and ride to the palace in Kabul’, and I basically said to him, just do it, and it was up to us to shoot the right moments. Even though it’s staged, it’s nothing that I invented. It’s his life, and it’s very close to his natural behaviour.

It seems like you play not only with form, but also with time. The Land of the Enlightened opens with the creation myth of Afghanistan, the children feel like they could be from any time, but they play in, and make a living from, the tanks and mines from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, while the presence of the American troops speaks of a much more recent history. Within all of this, there are time lapses showing us the passing of the clouds and the arc of the stars. It’s like the earth is spinning and we are reminded of the depth of geographical time and the enduring nature of the land of Afghanistan itself, which witnesses histories repeatedly played out upon it.

Time was something very important to me. What I was trying to say is that the universe is still deciding how all of us will live. It’s much more powerful than our lives. I wanted to show this in Afghanistan but I think it applies everywhere. The history of what happened in Afghanistan is particularly important to tell however. The reason why I use the Russian song when the Americans are leaving is that the experiences of the Soviet army when they were in Afghanistan, are so similar to the experiences of the Americans. They were both trying to protect the border with Pakistan and prevent the Taliban from infiltrating, and they both had the same nostalgia towards Afghanistan. We even went much further than that and brought an ex soviet soldier back to his old outpost in the middle of the mountains. He spoke about his experiences and reflected on the war with the Americans. But it was a storyline that was maybe too layered and too complicated, and the broadcaster ARTE, asked for this storyline to be cut, as they thought that many people would not understand what happened during the soviet war. But the layers in the film are important to me.

Cinema itself is something that the Taliban are against and they have banned films and shut cinemas, and while making the film you were attacked, so it was obviously dangerous at times. What were the ethical considerations, when you were involving local people, including children, who have to live in their country after the film is released? Was that an issue and if so, how do you deal with that?

In many of the areas in which we were filming, there was no electricity so most of those kids had never seen television before, they had never seen a phone with video on it, and they had never seen cinema, and in most cases they had never seen a film camera, so I remember some of the kids saw our film camera and thought it was a rocket launcher, and they were really afraid. So the first challenge was to make them understand that the camera belonged to us and that it was trying to make an image, but we could not show them the image as we were shooting on film. So most of those kids never understood what we were doing. They thought it was some sort of game.

We are going back to Afghanistan in August and we are going to show the film in Kabul for the crew and for the ministries and some embassies, and then we are going to go back to the mountains, with a mobile cinema, and we are going to screen the film for them. The security now in Afghanistan is much worse than a year ago as NATO is withdrawing from the bigger cities and the Taliban is taking over much more terrain so it may be tricky, but security wise I don’t think there will be a problem. I don’t think the Taliban will threaten the kids who cooperated with us as they are not going to see the film and try to figure out who worked with us.

The main problem is that the economical situation in Afghanistan is so bad that I am receiving messages all the time from Afghan assistants who worked with us on the film who say ‘sorry Pieter but you have to help us. We did so many things for you and for this project and now everybody is without a job for more than a year’. Last week I talked with my first assistant who said ‘I now have a choice. I need to find work or I go to Pakistan to sell bananas or I join IS to fight in Syria’ and its only due to a lack of money. it’s an absurd situation. Even those who adhere to Shia islam are going to join IS which is completely salafist, Wahhabist, and Sunni. Several friends of my first assistant have already died in the war in Syria just because they wanted to help their families. And it’s also very difficult for me to say ‘I know I counted on you for 8 years but what can I do? I can’t invite you all to Belgium.’ I said that I’m going to come back to Afghanistan this summer and I’m going to hire them all again, but it’s a difficult thing.

What do you hope to discover when you show the film to children who have never seen a film before? Do you have any idea of what you would like to see or find out?

Last year I was in Afghanistan for a very short time to record the voice over of Gholam Nasir, and I showed him a rough cut of the film. He was intrigued: laughing, and crying and clapping his hands, so I expect that lots of different emotions will come out. I think it’s going to be a very beautiful ending of the film about the making of The Land of the Enlightened. These kids who worked for such a long time on this film can finally see themselves on screen, and hopefully they will then understand what we were doing.