If Paddy Considine’s film existed within the world of 30 Rock it would be his bleak directorial debut not Tracy Jorden’s Oscar bait urban drama that would merit the title Hard to Watch. For in truth here is a film that traverses the crooked depths of broken and forgotten existence. It’s an auspicious debut from Considine who deftly blends moments of humanity and inhumanity to exhibit a powerful and moving picture of life fallen through the cracks.

If Paddy Considine’s film existed within the world of 30 Rock it would be his bleak directorial debut not Tracy Jorden’s Oscar bait urban drama that would merit the title Hard to Watch. For in truth here is a film that traverses the crooked depths of broken and forgotten existence. It’s an auspicious debut from Considine who deftly blends moments of humanity and inhumanity to exhibit a powerful and moving picture of life fallen through the cracks.

Peter Mullan plays Joseph an irascible and mentally itinerant widower prone to fits of rage. As he stalks what are obviously his old stomping grounds it’s apparent that he’s a monster past his prime – a Tyrannosaur himself – but a fossil no longer the tyrant he once was. Now there are much nastier, younger thugs who have dethroned his alpha status in the community. Seeking shelter in a charity shop one day he encounters Hannah (Olivia Colman) a kindly but tortured soul and her offer to pray for him begins an unlikely friendship that sparks moments of warmth in an otherwise cold abyss and begins to unearth the qualities of their lives which both have kept hidden.

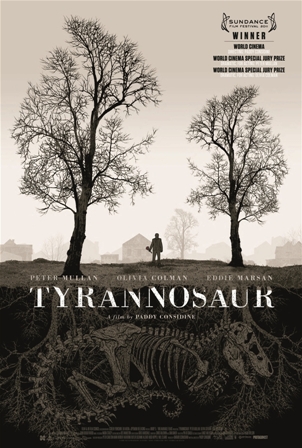

The notion that this is a film about what’s beneath the surface extends throughout the whole piece. The theatrical poster could not be clearer. We all have skeletons in our closets; bones we hide beneath the surface in the hope that if we bury them deep enough we might forget they’re there at all. For Hannah it’s her horribly abusive relationship with her husband (Eddie Marson) hidden behind prim suburban doors. And for Joseph it’s the tender heart revealed when we glimpse the husk that is his featureless home. But more than this – and similarly to Joe Cornish’s directorial debut Attack the Block – it’s about not judging people and indeed an entire area on its surface waters alone. The time we spend with Joseph and Hannah reveals reservoirs of emotions and rifts of abuse that have poisoned their present actions. These cause us pause for thought; and in similar fashion a horde of donations left outside Hannah’s charity shop displays that there too is good in the area despite its dilapidated appearance.

Considine exhibits a rich ability for capturing the essence and mind of a character. Several scenes stand out in this regard. A particularly misery laden one in which Joseph, after destroying his outhouse, sits kinglike atop the ruins, the destruction born of his own making. And another in which Hannah’s shop assistant duties call her away from a moment of shaking tears. As she moves through to serve her customer the camera stays in the back of the shop where surely Hannah also still is and instead looks out at the transaction. It’s a small and neat bit of contained camerawork that evokes the notion that there is a side we present to the world around us and a side that is truly ourselves. For Hannah the real her, the terrified, shaken and broken Hannah remains in the back, and we stay with her.

What’s most remarkable though is the way the film neatly oscillates between despair and hope and by bringing its two characteristically different but situationally similar leads together achieves a first step towards – albeit bittersweet – redemption. Bleak but moving, powerful and poignant this is challenging and affecting storytelling that will leave you gut punched and questioning your perceptions of the world around. For in truth Joseph’s speech about the mistreatment of dogs rings true for humanity as well and as Hannah displays there is only so much abuse and humiliation a being can take before it snaps, before it becomes a true victim of its own oppression; and how many of the misdeeds of the world could this account for?

This is a picture of life at its most sobering, inglorious and isolated. Indeed the only sign of outside institutions or help comes at the climax of the film and even then they are the opposite of those intended to aid, that institution which kicks in as a last resort. But what resonates most strongly here is the sheer humanity on display. Considine and his leads have worked incalculably hard to convey empathy to characters who are demonstrably outside the spectrum of human kindness or caring and catalyse in us those exact emotions. Mullan is a black hole, a self-destructive burden upon himself and others but manages to eschew our aversion through infusing a tender vulnerability and dogged pursuit of bettering himself. And Colman devastates through her inimitable portrayal of quiet dignity while all the time teetering on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

The resulting unease and starkness that comes from witnessing such a stripped back picture of life at the bottom of the food chain builds crescendo like into an explosion of injustice and an uncompromising dedication to realism – simply put it’s an absolutely absorbing and deeply devastating debut that’s nothing short of brilliant.