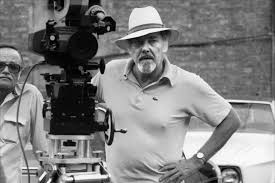

“Filmmaking is a chance to live many lifetimes.” So said Altman and his expansive, prolific and diverse output has lead his viewers on a rewarding journey into a variety of people’s lives, in ways which were fresh, insightful, provocative, truthful, innovative and intimate.

“Filmmaking is a chance to live many lifetimes.” So said Altman and his expansive, prolific and diverse output has lead his viewers on a rewarding journey into a variety of people’s lives, in ways which were fresh, insightful, provocative, truthful, innovative and intimate.

This documentary by Canadian director Ron Mann is equally intimate and insightful, focusing on Altman’s maverick role as the challenging antithesis to Hollywood artifice and corporatism. As he also said of Hollywood and in the film: “They sell shoes and I make gloves.” And as Bruce Willis says of him when asked to describe what Altmanesque means (the film asking this of various familiar Altman players throughout the film including Elliott Gould, Lily Tomlin, Julianne Moore and poignantly the late great Robin Williams): “Kicking Hollywood arse.” And we thank him for making such good gloves and kicking that arse dearly.

As the father of American independent cinema alongside directors such as John Cassavetes and Hal Ashby (surprisingly contemporary indie directors are not mentioned in this film, the one big omission), he really set out to make films that broke the mould whilst engaging audiences: Lon g scenes of overlapping dialogue, incidental dialogue (Tarantino must’ve been taking notes) long takes, improvisation, ensemble casts, multiple plot-lines, ambiguous endings, naturalistic acting, these are devices that have become common.

g scenes of overlapping dialogue, incidental dialogue (Tarantino must’ve been taking notes) long takes, improvisation, ensemble casts, multiple plot-lines, ambiguous endings, naturalistic acting, these are devices that have become common.

But when Altman was starting as we learn early on, he got fired from jobs for trying to make something real, as Jack Warner is memorably quoted as saying in the film about his methods, after working at Fox: “That fool has everyone speaking at the same time.” Little did Warner know too that his methods for mixing dialogue on separate channels so the director could control the mix, forcing the audience to decide which character to listen to, would become industry standard.

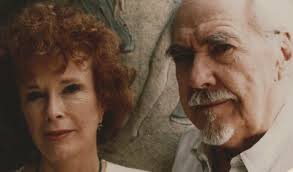

Mann show too the costs of being such a maverick with Altman and his family, wife and stalwart rock Kathryn Reed (who narrates much of the film, adding to the film’s intimacy), and sons Bobbie, Mike, Matthew, Stephen, and daughter Christine having to suffer the deprivations of periods where Altman was out of work (true to his maverick form we learn that Altman gambles his money on a horse race and casino to make extra money, luckily winning). We also learn that while he was a avuncular, sensitive and sympathetic director who treated his actors as the most important elements of his films and encouraged a family-like atmosphere where everyone contributes (in direct contrast to auteurs like Hitchcock), he was largely an absent figure as his son Stephen relates due to being such a workaholic, and he really did work up until the very last moments of his life. As he said of both his open-ended films and the possibility of retiring, death truly was the only real ending for him.

Mann show too the costs of being such a maverick with Altman and his family, wife and stalwart rock Kathryn Reed (who narrates much of the film, adding to the film’s intimacy), and sons Bobbie, Mike, Matthew, Stephen, and daughter Christine having to suffer the deprivations of periods where Altman was out of work (true to his maverick form we learn that Altman gambles his money on a horse race and casino to make extra money, luckily winning). We also learn that while he was a avuncular, sensitive and sympathetic director who treated his actors as the most important elements of his films and encouraged a family-like atmosphere where everyone contributes (in direct contrast to auteurs like Hitchcock), he was largely an absent figure as his son Stephen relates due to being such a workaholic, and he really did work up until the very last moments of his life. As he said of both his open-ended films and the possibility of retiring, death truly was the only real ending for him.

Although rare home movie footage of the children, including a clip where they pretend to be in a silent Western, suggests that the children loved being his actors too (and later on as the sons joined his crew they love the chance to be paid and spend time with their dad). It is a fact he also makes up for much later in life, and we see him paying touching tribute to his family who allowed him to make the films in his much deserved Oscar lifetime award acceptance speech.

Ultimately this documentary makes you remember just how masterful and unique films like MASH, McCabe and Mrs Miller (in the film we hear the voice of renowned film critic Pauline Kael eloquently eulogising that particular ‘pipe dream of a film’) The Player, Short Cuts and Gosford Park were. It also makes you want to revisit these films, with well-chosen clips putting you back into those rich worlds he created (I for one am going to have to re-watch Gosford Park and definitely see The Long Goodbye).

film we hear the voice of renowned film critic Pauline Kael eloquently eulogising that particular ‘pipe dream of a film’) The Player, Short Cuts and Gosford Park were. It also makes you want to revisit these films, with well-chosen clips putting you back into those rich worlds he created (I for one am going to have to re-watch Gosford Park and definitely see The Long Goodbye).

Long may his films be watched and celebrated, and long may directors like the great Paul Thomas Anderson (who was also his standby director on his last film) follow in his generous footsteps.

Showing in selected cinemas now.