“There never was a woman like Gilda!” screamed the poster at the time, and time seems to have kept that idea strong. We need simply look at two films commonly cited as ‘modern classics’, The Shawshank Redemption and Mulholland Drive, to see the image of Rita Hayworth’s slender, bare-shouldered silhouette immortalised as the sexual feminine ideal. Beyond Gilda herself, though, what is there to Gilda? Film historian Eddie Muller puts forward a good case in the most valuable supplement of Criterion’s latest UK release, discussing the “strange and perverse” nature of the film as one where “subtext is the plot” and digs into the relationship between the film’s two main male characters as coded in homosexuality, alongside a feminist reflection of Hayworth’s managed career motivated by the film’s female producer Virginia Van Upp.

In terms of production, Gilda is a luscious example of Hollywood glamour, film noir shadows infected with Hayworth’s glamour and the political rawness of the post-war era. Hayworth’s costumes are iconic for how much skin they reveal, the camera frequently framing her from bust upwards so that the audience are teased with the illusion of Gilda’s nudity. In terms of a fiery rebellion against the restrictions of the time, Gilda feels cheeky and fleet-footed. But the film becomes leaden with the stilted presence of leading man Glenn Ford, stuck in restrained tough guy mode and, if we understand the film as Muller does, given a character whose identity is in a conflict Ford probably wasn’t clued in on.

It does seem to be a film so sodden with subtext that it forgets to ensure the text itself is coherent, and it comes off like a cross between the gloomy romanticism of Casablanca and the baffling machinations of the same year’s The Big Sleep. Yet Gilda remains eminently watchable thanks to Gilda herself, because Hayworth, from the moment she whips her hair backwards into the frame, is such a vivid presence, lithe with contradictions, acting like a femme fatale because life has hardened her, but immediately eager to be tender and affectionate when opportunity presents. Next to the stiffness of Ford, Hayworth’s lithe physicality and tart humour are eternally striking, and fittingly, it is she that has made Gilda immortal.

Extras

Extras

Gilda is sparser on the supplements than some of the recent releases, but they are at least consistently rich in value. As mentioned above, Eddie Muller’s new interview is the release’s most intriguing supplement, digging intelligently into the film’s coded meanings and the motivation behind the creators. Richard Schickel’s audio commentary, brought over from the 2010 US Criterion release, is sparser and more measured in its commentary, but his gravelly voice brings a relaxed, inviting timbre to a track worth the time.

Again recorded in 2010, an appreciation of the film by Martin Scorsese and Baz Lurhmann emphasises the impact of the film, and Hollywood’s Golden Age in particular, on two of the most inventive and vibrant filmmakers of modern cinema. Rounding off the collection is an old curio, ‘The Odyssey of Rita Hayworth’, an episode of a 1964 series called Hollywood and the Stars narrated by Joseph Cotten, best man at Hayworth’s wedding to Orson Welles. Opening with the rhapsodic declaration that “she was the first Hollywood stars to be called a love goddess”, the episode is mostly an infatuated celebration of Hayworth’s life and career, taking us from her childhood to the unstable moment of the 1960s with a combination of Cotten’s incisive baritone and Hayworth’s own remarks, hovering sensually over the images.

The supplements are rounded off by an original trailer and a booklet essay by film critic Sheila O’Malley.

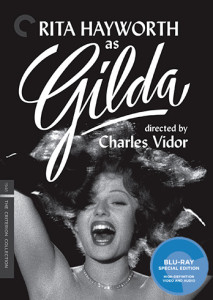

Gilda is now available on DVD and Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection.