Vaclav Marhoul’s adaptation of Jerzy Kosinski’s notorious novel opens with the young protagonist getting chased down by bullies, who beat him and set his pet possum on fire. It’s a merciless way to start the film but it sets the tone perfectly, and it only gets worse from there. An hour into the film, any vestige of hope has gone, and there is still 2 hours left. The film is just as controversial and gruelling as the book, and while the horrors of war are conveyed vividly and with realistically, the point of the story often becomes mired in relentlessly bleak misery.

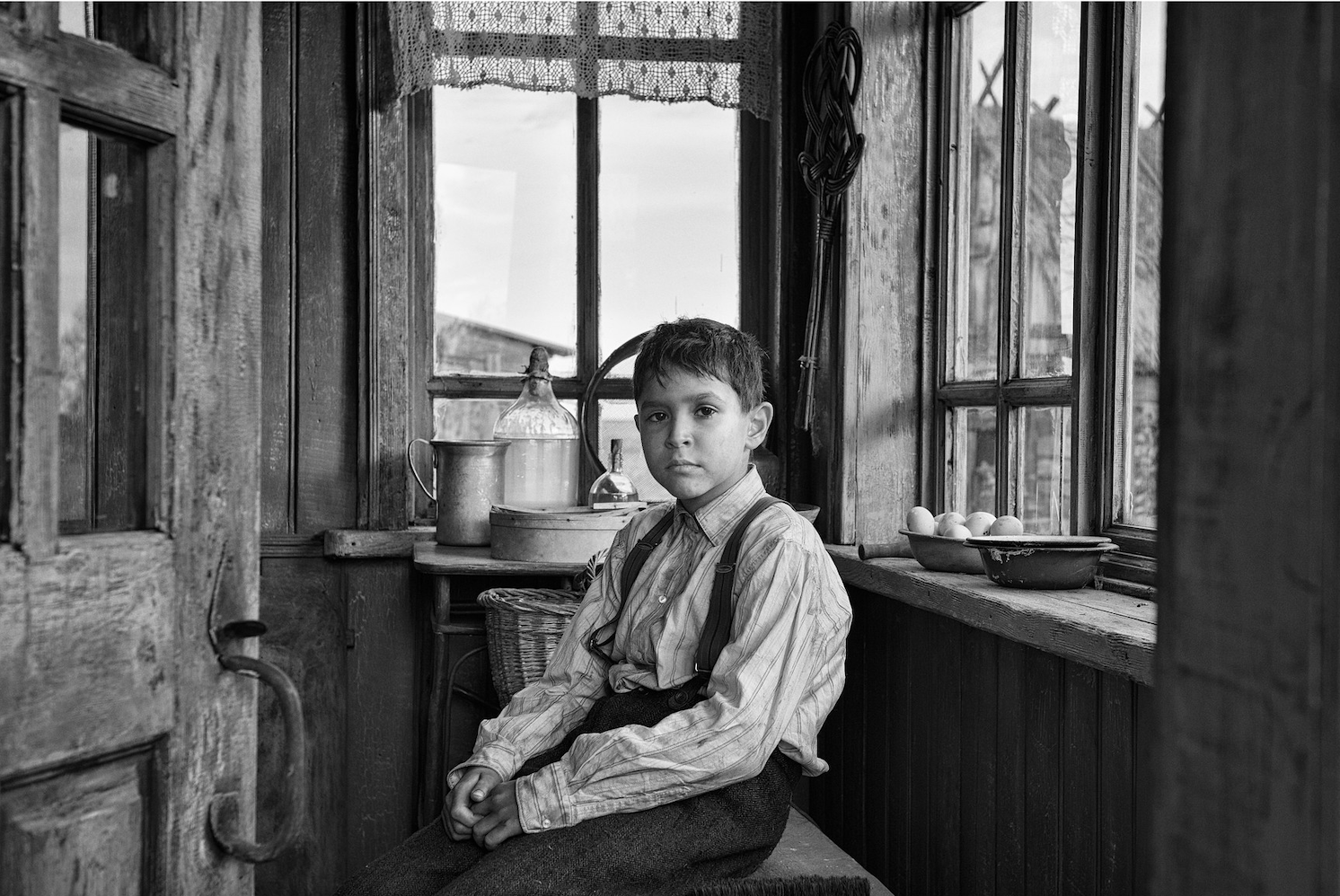

The story of a boy (Petr Kotlar) as he tries to survive in wartorn Eastern Europe, having to contend with barbaric actions of soldiers and civilians alike. Essentially taking the form of 9 chapters, named after the characters the boy encounters on his journey, The Painted Bird plays out like a series of horrific vignettes riffing on the horror of war, and how it brings out the absolute worst in people.

Visually, it’s breathtaking. Marhoul’s use of black and white cinematography is beautiful, and calls to mind the composition of masters of European cinema like Michael Haneke, Andrei Tarkovsky (specifically Ivan’s Childhood) and Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes & Diamonds. The story clearly owes a huge debt to Elem Klimov’s Come And See, which treads a similar path, following a boy losing his innocence through the Second World War. However, Come And See is a sensory assault, putting the audience in the midst of the chaos, with numerous instances of humanity and compassionate behaviour, despite the horrific setting. The Painted Bird keeps you at arm’s length, resulting in a film that is more beautiful, but also less authentic, and oddly less humane than a film that is routinely listed as one of the most disturbing films of all time.

Traumatising as it is, Come And See is full of feeling. In comparison The Painted Bird feels devoid of emotion. There is a vitality to Come And See and Tarkovsky’s films, which means that even though they can be a slog to sit through, there is always something to enjoy. Marhoul’s film is quite sterile by comparison,

While Come And See is avowedly anti war, The Painted Bird seems to be anti-people, depicting almost every character as venal, barbaric and inhumane. In the world of the film, pretty much everyone is hateful and violent. The civilians are often complicit with the actions of the Nazis – in fact both instances of the Nazis interacting with the boy have much happier conclusions than the encounters with his own countrymen.

The relentless onslaught of horrors has a numbing effect, which may be the point but does result in a pretty thankless watch – there ‘s only so many atrocities you can watch before you get desensitized to it all. It also gets grindingly repetitive after a while, without appearing to actually progress, or develop it’s central character all that much.

Kotlar is brilliant as the boy though – his low-key, inscrutable style is a blank canvas on which the numerous atrocities are painted. And to the extent that his arc works at all is entirely due to his largely non verbal performance. The changes he goes through are subtle, but still present, and written all over his face by the films end.

The supporting performances are also generally great, but the few familiar faces do distract a little, especially when by and large they are a benevolent presence in the film. Stellan Skarsgard makes an impression as a kindly Nazi guard and Harvey Keitel gives the most humane performance he’s given in a while as a principled if ineffective priest. Meanwhile, Udo Kier and Julian Sands play two of the films most irredeemable monsters, but predictably only one of them gets their comeuppance – even if it is gratifyingly nasty.

This is still a technical marvel, with some perfect composition, and Marhoul deserves all the plaudits being thrown his way for this. The film is meticulously put together, and almost every scene would be the most disturbing scene of any other film. The sequence showing Polish Jews breaking out of a moving train, only to be nonchalantly machine-gunned by the watching German soldiers, is horrific but ingeniously constructed.

It is possible to show graphic brutality and still temper it with some sense of hope, or have some sort of point, or even just give the audience a reason to keep watching. Last year’s The Nightingale had some utterly horrific scenes in it, but worked, due to the touching central relationship. There is no such respite here. There are small moments of tenderness – Barry Pepper’s unflappably cool Russian sniper giving the boy a gun, and the final little coda on a bus are nice, sensitive touches – but overall it’s not enough to warrant the torturous run time, and the few friendly faces are gone too quickly to make an impression.

The war crimes enacted in Eastern Europe during WWII are still woefully underrepresented on film and even in wider discussions about the war, so any renewed interest this film generates is more than welcome. However The Painted Bird handles it in an overly nihilistic, gratuitous way. It’s a necessarily tough watch, but even with this caveat it’s overwhelmingly bleak. While it feels like the spiritual successor to Come And See in it’s depiction of brutality, The Painted Bird lacks the basic humanity of that film. Full of brutal imagery and beautiful cinematography, it’s one of the bleakest and most disturbing films of the year. It’s unforgiving, relentless and not a film I’ll be revisiting any time soon.