Any time spent furthering my knowledge of Werner Herzog’s work is time well spent and so the chance to see

Herzog’s 1979 take on Nosferatu i.e Dracula-which will be showing as part of the BFI’s exciting Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film season- was too good an opportunity to miss. And having seen the F.W. Murnau film and thinking that it was culturally interesting but not as great as everyone said it was I really wanted to see what Herzog would be able to contribute to this well-worn tale.

It should be noted that for Herzog the film was not meant to be a remake of Murnau’s film (thankfully) it was as he puts it an “entirely new version” and for me, blasphemous as this may be, it really was a much more interesting, soulful and memorable version of the Dracula story than Murnau’s film or indeed many of the other vampire films I’ve seen. For a start there is much more emphasis on characterisation and with Herzog’s fascination with social outcasts, it is no wonder that Dracula becomes a much more involving, complex and human character than Murnau’s theatrical one-dimensional evil monster.

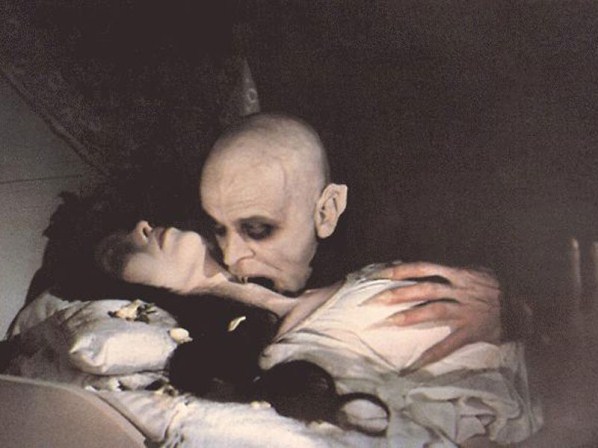

This is also testimony to Klaus Kinski’s bravura performance, imbuing the vampire with pathos, yearning for love and human warmth, which he can convey in a single look, and adding a real sense of melancholy to his lines about the tedium of immortality. While also retaining animalistic behavioural tics that mark his otherness; hungrily eyeing Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz) in the famous scene where Harker cuts himself with a bread knife and Dracula rushes to suck his bleeding hand, and breathing heavily and intensely as he pursues him after (the eerie sound design in the film is one of its highlights) or lustily staring at Lucy. As Herzog points out himself although Klaus is only on the screen for seventeen minutes in a film that lasts almost two hours, he dominates the film and his is a presence impossible to forget.

Isabella Adjani as Lucy also fascinates with her obviously haunting beauty, expressive almond -shaped eyes, and the way her pale face is framed against her thick dark hair. But aside from her looks she perfectly channels Greta Schroder’s (Murnau’s Lucy) agonised expressions without looking ridiculous, and is the perfect picture of angelic innocence (in direct contrast to Nosferatu) as she plays with kittens in a romantic white lace dress and fawns lovingly over Harker at the beginning of the film. Adjani also adds a real sense of foreboding as she pleas desperately with Harker not to visit Count Dracula after having morbid nightmares and visions, and we see her listlessly staring through a window as she contemplates Harker’s fate away from her (a mesmeric image that could almost be a painting). She also embodies well a developed sense of determination and strength to counterbalance all that Victorian girlish innocence. As Lucy resolves by the end of the film to kill Dracula seeing the damage that Dracula’s plague has brought to her town of Wismer and ignore the advice of Dr. Van Helsing (Walter Ladengast); who argues that the urgent situation must be resolved slowly through science (once again Herzog satirises the dismissive arrogance of scientific people as he did so well in The Enigma of Kasper Hauser(1974)).

Isabella Adjani as Lucy also fascinates with her obviously haunting beauty, expressive almond -shaped eyes, and the way her pale face is framed against her thick dark hair. But aside from her looks she perfectly channels Greta Schroder’s (Murnau’s Lucy) agonised expressions without looking ridiculous, and is the perfect picture of angelic innocence (in direct contrast to Nosferatu) as she plays with kittens in a romantic white lace dress and fawns lovingly over Harker at the beginning of the film. Adjani also adds a real sense of foreboding as she pleas desperately with Harker not to visit Count Dracula after having morbid nightmares and visions, and we see her listlessly staring through a window as she contemplates Harker’s fate away from her (a mesmeric image that could almost be a painting). She also embodies well a developed sense of determination and strength to counterbalance all that Victorian girlish innocence. As Lucy resolves by the end of the film to kill Dracula seeing the damage that Dracula’s plague has brought to her town of Wismer and ignore the advice of Dr. Van Helsing (Walter Ladengast); who argues that the urgent situation must be resolved slowly through science (once again Herzog satirises the dismissive arrogance of scientific people as he did so well in The Enigma of Kasper Hauser(1974)).

While Bruno Ganz (so superlative in Downfall (2004)) does a good job of conveying Harker’s resolute foolhardiness and subsequent vulnerability trapped in a desolate ruined castle. And Roland Topor as Renfield is memorable for his larger-than-life performance and manic laugh which comically punctuates almost every line of his dialogue and makes Harker look even more naive for accepting his commission to see Dracula. (The comedic nature of this overly obsequious character and his relationship to Dracula is also brought out in a memorable scene in which Kinski impatiently brushes him away and commands him to go to Prague after Renfield implores that he will do whatever he commands).

The film is also full of startling imagery, courtesy of cinematographer Jörg Schmidt-Reiwen, that stays in the mind long after viewing, like the dramatic opening where the camera lingers on mummified people caught in their death throes to the sound of a heartbeat, in one of Lucy’s nightmares. Then there are the cleverly placed blue-tinted slow-mo shots of a bat in flight (actually found footage from a scientific documentary) that suggest the vampire’s powerful presence even when he’s not there. Or the landscape shots of the intimidating High Tatras Mountains of Slovakia (standing in for the Carpathian Mountains) framed from a low angle as a vulnerable abandoned Harker sits on a rock like a Romantic poet. Or the recurring shots of the spectacular ruins of Dracula’s castle on top of a desolate hilly range and the omniscient slowly gliding panoramic shots of Wismar’s town square in chaos from the plague and filled with townspeople dancing with animals, drinking and feasting as they carpe diem. As well as the numerous shots of the rats which overrun the town, teeming through the streets and adding to the sense of evil consuming the town (fun fact: Herzog apparently used 10,000 white rats which all had to be died grey). I could go on but needless to say the film is a visual feast. And these fantastic images are also accompanied by the fantastically atmospheric and epic music of Popol Vuh (using male choral voices to great effect) accentuating the atmosphere of monstrous evil, death and destruction.

This is a film to terrify, mesmerize, move and even laugh at, and most importantly to re-invigorate your faith in the power of cinema, miss it at your peril.