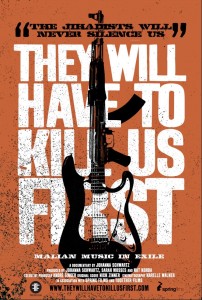

Music is the beating heart of Malian culture, but when Islamic jihadists took control of northern Mali in 2012, they enforced one of the harshest interpretations of sharia law in history: They banned all forms of music.

Music is the beating heart of Malian culture, but when Islamic jihadists took control of northern Mali in 2012, they enforced one of the harshest interpretations of sharia law in history: They banned all forms of music.

Radio stations were destroyed, instruments burned and Malis musicians faced torture, even death. Overnight, Malians revered musicians were forced into hiding or exile where most remain, even now. But rather than lay down their instruments, the musicians are fighting back, standing up for their cultural heritage and identity. Throughout their struggle, they have used music as their weapon against ongoing violence that has left Mali ravaged.

They Will Have to Kill Us First sees musicians on the run, tells the story of the uprising of Touareg separatists, reveals rare footage of the jihadists, captures life at refugee camps where money and hope are scarce, charts perilous journeys home to war-ravaged cities, and follows our characters as they set up and perform at the first public concert in Timbuktu since the ban.

“Not everybody in this film made good decisions. Some made very bad decisions. I don’t judge them for that at all. You can’t know what you’re going to do when you’re in a war zone. You can back the wrong people… all kinds of things can happen, and you just don’t know”, director Johanna Schwartz tells Greg Wetherall.

How do you go about putting a film like this together?

The whole film happened so organically. It wasn’t like it was hugely premeditated. I was planning my trip to Mali as a tourist to go to the festival in the desert, because I had been a fan for many, many years. A friend of mine had just relocated to Mali for work. I thought, ‘that’s it, I’m going. This is going to be fun: we’re going to have a party’ and that was when the conflict totally flared up and music was banned. I was in midst of planning my trip, so I just thought screw that, I’m going to go anyway. The whole thing was ‘bang, bang, bang, react, react, react’ and, in a way, the whole film was like that. It was just this incredible organic experience.

I think that the thing that I knew that I needed to do if this was to work was to find characters that could tell different sides of the story. It’s not as though there’s just one story coming out of Mali. Not every musician responded the same way to the conflict. There were so many complexities on the ground. I knew that if I found the right characters, that the film would write itself.

On the very first day of that first trip, we met (famous Malian musician) Khaira Arby. That’s really unusual; to meet one of your main characters on day one. It was unbelievable. On the next trip, we met someone else. The fourth trip we met Songhoy Blues (up and coming Malian band). They had just formed the band. Everything just came together. It was like there was this shining star over this project.

Did you worry about your own safety?

When you work in a war zone, it’s peculiar, because you perceptions shift. I felt fine in Bamako, because there hadn’t been an attack in Bamako. Now, there has been. At that time there wasn’t. I was pregnant for the whole first half of filming, so that was another thing altogether.

Were your family worried?

Well, I just went! This entire film was like a train powered by willpower. I don’t know where it came from inside me, but we were pushing that train forward against the wind the whole time. I love adversity and I love when I can’t actually do what I want to do, because you come up with way better stuff!

Did you discover Songhoy Blues through the community?

Did you discover Songhoy Blues through the community?

It was through Andy Morgan, who is a wonderful, wonderful journalist and the original manager of Tinariwen. He’s been on the Malian music scene for a very, very long time. He was one of the first people that I contacted when I started the project. I knew that I needed Andy’s help. I couldn’t do it without Andy, so I kept pulling him in more and more and more! Andy was the first person to interview Songhoy Blues after they were discovered by Africa Express and it was Africa Express who they auditioned for and it was really through them, and that organisation, as to how I found out about them.

Is it a coincidence that a lot of the components that make for political and theological disruption, unrest and upheaval, actually contributes to a richer musical heritage?

One of the things that a lot of the musicians said to us was that the reason why the extremist groups that came in attacked music specifically, they thought, was because music was the thing that was keeping everyone vaguely together. Obviously, there was a lot of internal strife in that country. You have MNLA (National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad), mostly Tuareg group, up in the north wanting their autonomy, then you have the black Africans in the south. Because music took all of these things and put them together, music was holding the country together! So, of course, if you have this group comes in from the side and wants to destabilise the country, you’re probably going to attack the music.

Was it hard to work out where the film would end?

We had no idea how it was going to end! We had all these endings; we thought that maybe the film would end with their tour around Europe or maybe it would end another way. Then, Khaira said, I’m bringing music back to Timbuktu. We were like, that’s our ending, but will she be able to pull it off. Until we were actually there in Timbuktu filming her and she was singing, I didn’t know if it was going to happen, because at any time there could have been an attack. There could have been something and the whole thing would have gone ‘whoosh’ (gestures going up in smoke). I’m really pleased that it ended positively. I really thought there was going to be a downbeat ending, but in the end there were so many wonderful and positive things about this film.

Did you wrestle with the decision to show the footage of the hand being chopped off?

We had footage that that was a lot worse than that. That was the footage that we had the biggest discussions in the edit suite. Everyone was wading in with ‘should we or shouldn’t we’ show it. In the end, we decided to show it. We thought it was important for people to understand what was happening, but we decided not to show stuff that was so horrific that it would distract you from the whole film. It was trying to find that line.

What inspired you to get into documentary films?

I’m American and I grew up watching PBS. PBS was very much the home of documentary and I absorbed all of it. Funnily enough, I’m probably inspired more by narrative film, even though I love making documentaries.

Do you think you’ll stay in documentaries?

I think so. I really like the chaos of it. It’s total chaos! That’s where all the magic happens! A documentary is like one big long (music) jam!

They Will Have To Kill Us First is in cinemas from 23rd October 2015