Set in the Jordanian desert, against the backdrop of the Arab revolt of 1916, Theeb is, as first-time director Naji Abu Nowar puts it, a ‘Bedouin Western’, but one with a beautifully crafted coming of age story at its heart. Filmed entirely on location, and with a cast of Beduoin non-professional actors (none of whom had been inside a cinema before), it features mesmerizing performances, in particular from the young Jacir Eid in the title role. Abu Nowar, who earned the Orizzonti Award for Best Director in the Venice Film Festival, lived with a Bedouin tribe for about a year as he developed the film. Front Row Reviews sits him down to talk about the process he and his cast and crew embarked on.

Jacir Eid as Theeb

Can you describe how the screenplay began to take shape?

When you develop something like this, you are constantly changing it. The story is constantly growing in different directions. Originally the film started as a full on Western. A Bedouin Western, taking archetypes of the genre and using them. But then we realized that was the wrong way to go and we created a rule, which was that you never apply an element of the genre to the story without there being something within Bedouin culture or history that mirrors it. You can never impose it. That was the major shift that happened where it really started to take on a shape that was more Bedouin. And that’s where their storytelling really came in – for instance the idea of taking the circumcision ceremony of a thirteen year old boy and the trials of moving from boyhood to manhood and using that. In the film, the revolt and the changes in the geo-political environment initiate these challenges for the boy, so we are able to have an existential crisis for the main character and also one for the society. They mirror each other. It took an awful long time to put all these different things together and develop the screen play – about two years.

Jack Fox as Edward rides into Rum through the sikh

My niece is a novelist and she also comes from a very traditional tribe and one of the things she said to me after the first or second draft of the screenplay was ‘you are writing this boy as yourself, as someone who lives in a modern state with the rule of law, but this is not that character. This character is a child who grows up in a very harsh environment. He grows up in a tribe and the tribe have these rules and he is going to be a lot more thick-skinned. He is going to be a lot tougher.’ And you start to realize that really you have to get down there and observe the people and learn from them as really it’s just not cutting it, writing from your imagination or from a history book.

Director Naji Abu Nowar plays acting games during the first week of workshops in the team’s house in Shakriya, Jordan

So thats when you started spending time with Bedouin groups, eventually making the move to go live with one for nearly a year. Did you know much about Bedouin life before that?

Not really. I knew surface stuff and I knew some cultural elements from stories my father used to tell me. So I knew some of the most famous folktales and some of the most famous cultural laws, like hospitality, and most Arab people know those famous stories and those laws, but to get into the intricate legal matters of, for instance, the law of protection and how that works and how seriously they take it – it’s unbreakable, that shocked me. And when you are living there you see how fragile you are and how easily you could die at any minute because you don’t know what you are doing. And so to then see someone standing next to you and to watch them manipulate their environment and thrive in it, it’s a very surprising and magical thing.

Jacir Eid as Theeb stares into the labyrinth of Rum

I heard that you workshopped stories and characters with the Bedouin before shooting. Can you talk about that process?

It was a sort of a secret auditioning process. We never told them what the story was until about two months or a month before we shot so they knew they were going to be in a film but they didn’t know what the story of the film was they didn’t know who the characters were. I didn’t want people giving favoritism to any one character or trying to behave in front of me like they were the right person for that character. Instead we used a technique by Augusto Boal, which is also used by Hisham Suleiman, the acting coach who taught us to teach them. And what you do is you find these role-playing scenarios; things they can relate to so that they can have an anchor or something that is real to them. If I do something about someone skipping the queue to take tourists on guided tours, everyone knows what I’m talking about there and everyone can relate to it. It actually might be a raw thing for them, they might have just had it happen to them yesterday and they are pissed off about it and want to get it out there in the open, to talk about it.

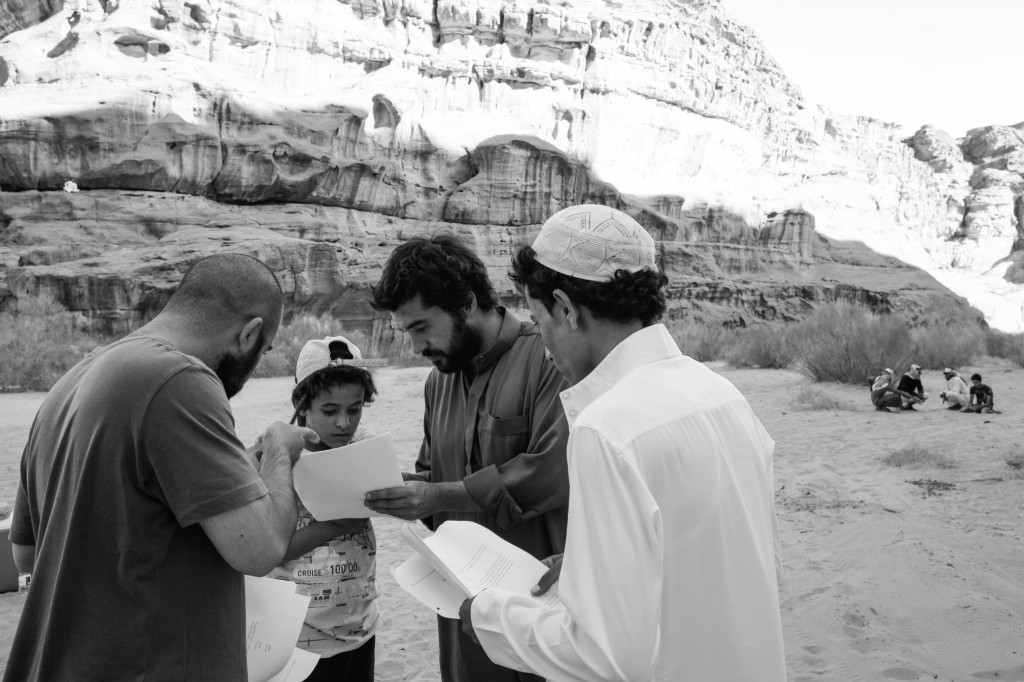

Workshop week 1 with Hisham Sulieman. Acting games!

What it also does is give me an opportunity to enter aspects of the characters in the film into these situations and see who works well in those types of roles. So for a character who is ambiguous like The Stranger, someone who is in a difficult moral situation, I find something similar from the modern world, but that contains a little less energy, and I put the character into that situation and see how the actors respond to it and see who does well in it.

We had eleven actors with us and one or two potential people for each role so over the course of three months we cast them. And the ones that didn’t get major roles, played minor roles. We had three potential actors for The Stranger and one of the reasons I thought Hassan Mutlag would work well in that role was that he looked like a classic bad guy yet he was one of the nicest men you could meet and I thought that if he could draw on his underlying kindness, he could give the character the depth and ambiguity that I was after.

Marji Audeh (The Guide) and the Theeb acting troupe perform trust exercises in the final week of the workshop with acting coach Hisham Sulieman

And Jacir, did you just know when you met him that he would be right for Theeb?

No, not at all. I had dismissed him very early on as he was very shy and I didn’t think he had what it would take to carry the film. But we needed to make a sort of video mood board in order to get money from investors and I asked my Bedouin producer to send me a kid of about 13 who could stand in for the role of Theeb. He was quite lazy so he sent me his son, Jacir, which I was a bit pissed off about really. But when we started shooting, something happened. It was magical. And I knew then that he was it, and we looked no further.

Jacir Eid (Theeb) relaxes between takes

So how long did you work with them in their roles?

Only a month while we were developing the dialogue together and as we developed the dialogue together we developed the roles together. So we were kind of rehearsing and preparing as we were doing the dialogue. For some, like for Hussein, who played the brother, it was just about making him feel comfortable on camera. My producer, Rupert Lloyd, had been filming all the workshops from the very beginning, and we made the rig bigger and bigger as the workshops progressed, so by the time that we were ready to shoot, he and most of the cast were already pretty relaxed on camera. With The Stranger, it was a lot more complicated. In the film he has a leg wound and so he was playing around trying different things (at one point he used ankle weights) in order to convey pain and build his character. With Jacir, the challenge was to get him to show heights of emotion, which he was reluctant to do. He would tend to laugh and giggle if he ever had to do something really serious, like striking someone or being terrified. He found it difficult to suspend disbelief. So Hisham Suleiman came at the beginning for four days and at the end for four days, and he did an amazing job in the last four days preparing Jacir. One of the things he developed with him was the technique of thinking about this teacher that he hated in school and Jacir then used that in the last scenes and it worked. It changed everything.

Jacir Eid during the first week of the Theeb workshops in Shakriya, Jordan

And did you spend a lot of time on blocking the scenes?

There is only one scene that is actually blocked. There is an action scene where there is a lot of shooting involved, and that involved a lot of movement. That was the only thing we choreographed and rehearsed a lot. I would shoot the rehearsals and work out what shots we were going to use. We also had to make sure we could manage it on sand – we put down chicken-wire so that the Steadicam operator didn’t sink into it. But apart from that, everything was very free. The rule was we shoot 360 degrees so the crew were always diving around hiding as we would literally turn wherever we wanted.

Steadicam Operator Doug Walshe lines up a shot using an improvised ‘camel rig’

So through this process of developing the dialogue and their characters, you developed the script?

We developed the script with them but then the question was, are you going to hand over a paper copy for them to look at? We did and it worked for everyone apart from one guy whom it virtually destroyed. So I took away the script for everyone apart from for certain very key scenes. We would discuss with them beforehand what the scene was about and if there was some key dialogue, we would rehearse that. But if it wasn’t key dialogue, it was always without the script. And because we had workshopped it and talked about it and developed the dialogue together they kind of all knew where they were going, apart from this one guy whom it destroyed. Even after taking the script away from him, he was still trying to remember it. That’s what I had to work with him on, trying to forget the script. It is a tough thing to judge. Will they thrive or will it ruin them?

Naji Abu Nowar discusses a scene on location with Jacir Eid (Theeb) and Hussein Salameh (Hussein) during the final week of the workshops

Was it difficult for you to let go of the script?For me the screenplay is massively important. Thats how I trained so its not that I’m in any way downplaying the importance of the screenplay, but the screenplay is a part of the process. It is not the be all and end all, it’s not a legal document that has to be rigidly followed. It is a starting point. Yet, you must work as hard and passionately as you possibly can to write the best possible screenplay that you can and you should feel that it is this legal document. You should be aiming for that but at the same time you should also allow yourself to be free to flow with any changes that seem natural and correct. For example we realised a week before we started shooting that we should mention the father who had died. And then when we were in post production we realized that we could go further and add certain ADR [Automated Dialog Replacement] lines that aren’t just little anecdotes, they are like the core of the film. For example when Theeb has the argument with his brother and he says ‘You are not my father’ or when he says ‘Remember what father told us – the strong and the weak’ those are ADR lines. That’s us going ‘oh we can do that there’. And then right at the end of post production, we asked the poet to write the poem as if it’s the father speaking to his son before his death, which is the opening sequence of the film. So the evolution of the story of the film is changing fundamentally even in post production.

Jacir Eid as Theeb and Hussein Salameh as Hussein in Theeb

We also had to change the screenplay as we were shooting, as we didn’t have enough money to shoot all the scenes. I shot 60 pages of a 90 page script so 30 of those were either cut, merged or condensed. There were scenes in the film that we shot and then I would have to add on an extra part to the scene. I was rewriting within the scene we had already shot. For example if we had shot scene 68 I would then have to, at night, work out a way that elements of 69 and 70 could be introduced to 68 and shot the next day and put into 68 without it looking odd. At 3 o’clock in the morning when you haven’t slept and you are really tired, its really tough to do that. For instance in the surgery scene, there is a gun being passed backwards and forwards and a knife being heated. That was actually three different scenes. The gun being handed over was originally in a hunting scene but we didn’t have enough time to do it and I had already shot the surgery scene so I had to find a way to merge that hunting scene with the surgery scene, so those elements were shot separately over different days but they actually look like one scene. That was really really tough and tough for the actors as well, but they did a great job.

Jacir Eid readies for a take

The performances in the film are incredible. Was achieving them your main focus or were the other elements of the film (the cinematography for example is beautiful) equally important?

I’m trying to make cinema. I’m trying to make a big grand film, so its not like I don’t want to block or to have big camera movement. But whats more important: a complicated blocking move or the core of a performance? Well for me it’s the core of a performance so if I’m using amateur actors, I have to forsake getting them to do some very complicated move. But I’m also kind of reeling from that as I want to make big films and that can be tough because you are compromising the entire time. But it comes down to what you want. Do you want performances or do you want camera work? Well, I’d hopefully get both but in this instance I couldn’t, so I chose performances as that’s key. But next time I will have the workshops for longer and I will include blocking from a very early stage so that it becomes second nature to them. The idea will be to essentially create an acting school. We won’t be using non actors and getting them ready to shoot, we will be creating our own acting school.

Cinematographer Wolfgang Thaler and Director Naji Abu Nowar discuss the framing of Hussein Salameh in the next shot

So you are going to do it again?

Yeah. I want to do my own Seven Samurai or Zulu. I’m going to try to do a big action film with these guys. Train them. Have stunt workshops, fighting choreography, blocking. Everything.

You are actually upping this?

Yes. I’ll be workshopping women this time too, which is going to be difficult sociologically. There will have to be a system set up for supervision and making the families happy. It’s going to be tough.

You said some of the Bedouin had never seen a film before, so how did they understand what they were doing?

Well they just had fun and as it progressed through the workshops and then through the test shoot where we filmed some of the scenes they had written with us, they got it. They met all the crew, they saw how it was filmed and edited and then watched it and so they saw what the process was like before we shot the film. One of the guys was like ‘Naji why is this guy [the sound man with the boom] sticking a fox tail in my face? Tell him to get it out of my face.’ But by the end of it we were all pros and joking about it.

Cast from Theeb perform a scene in the military zone in Wadi Arabah which lies on the border with Israel, seen in the distance. The production had to obtain special permission to shoot here and had to be accompanied by the army at all times

Its not always fun shooting a film so what happened when things got tough?

By the time we came to shoot, they were just as invested in the film as we were and even though at times they were very tired and annoyed and some of them had had their fill and probably wanted to quit, they said ‘Naji we gave you our word and we are standing with you’, so they stayed. That was very touching, as the whole film could have ended.

The crew scrambles moments before a sandstorm tears through the set. Actor Jack Fox takes an inventive approach to finding shelter

Do you ever talk to them about what they got out of it?

I think it was just such an exciting journey. Now that they are settled, the whole area has become a conservation site so its illegal for them to hunt. Not only are they settled but all the activities that they used to enjoy have been taken away from them. Its not that they hunted animals into extinction, it was tourists who did that. Experiencing the magic of the desert has been replaced by sitting in a brick house in intolerable heat so for them it was a chance to reconnect with, and teach the younger generation, their culture. And also it was an adventure. It was exciting, it was fun, and they felt that they were doing something to honour their way of life. Now they are tremendously proud of the film. Most of the TV shows are like cowboys and Indians. Still. Imagine if the 1950s cowboy and Indian shows were being made today. You wouldn’t accept it now, but those kinds of things are still going on. They are showing Bedouin in that light, so to make Theeb was a chance to show people their tradition and culture. And it has affected things as now the drama series are coming down and hiring them as consultants and actors. The Stranger was a dialogue consultant on a drama series so things are shifting. Many have told me that making Theeb was one of the greatest experiences of their life. A lot of them call me up saying ‘come on when are we going to do it again?’

The Middle Eastern premiere for Theeb was held under the stars in Wadi Rum, where the film was shot. The Bedouin-style drive-in was held exclusively for the communities involved in shooting the film. For 99% of the audience it was the first time they had been to a cinema

Theeb is on release in selected cinemas throughout the UK and is available on Curzon Home Cinema.

Click here to view the Theeb trailer