Every Christie fan has a favourite Hercule Poirot, be he the classic original Austin Trevor, the seemingly-ubiquitous David Suchet*, the primmest-of-the-lot Albert Finney, the well-fed and slightly camp Peter Ustinov or even the cameo-weird Hugh Laurie (yes, honestly, in Spiceworld: The Movie).

Every Christie fan has a favourite Hercule Poirot, be he the classic original Austin Trevor, the seemingly-ubiquitous David Suchet*, the primmest-of-the-lot Albert Finney, the well-fed and slightly camp Peter Ustinov or even the cameo-weird Hugh Laurie (yes, honestly, in Spiceworld: The Movie).

The Poirot box set, due out on 20 January 2014, offers the three finest screen adaptations of Christie’s works, and not only the two most famous big-screen incarnations of the Belgian sleuth, but also the most extraordinarily stellar supporting casts.

Coming first chronologically is Sidney Lumet’s 1974 Murder On the Orient Express. Featuring turns from Ingrid Bergman, Vanessa Redgrave, Michael York, Sean Connery, Lauren Bacall and Anthony Perkins (to name only a small proportion of the cast), and directed by the luminary Lumet, creator of a body of work that includes Twelve Angry Men (another forensic mystery set in a confined space with a limited but exquisite cast), it certainly has the pulling power. The sumptuous setting of the elite railway carriages, the time-of-the-essence allure and suspense, the crime-of-the-century backstory are all there, but despite all this, even despite Finney’s fastidious timing, the story is rushed. In all, by rights, it should be a better film.

Coming first chronologically is Sidney Lumet’s 1974 Murder On the Orient Express. Featuring turns from Ingrid Bergman, Vanessa Redgrave, Michael York, Sean Connery, Lauren Bacall and Anthony Perkins (to name only a small proportion of the cast), and directed by the luminary Lumet, creator of a body of work that includes Twelve Angry Men (another forensic mystery set in a confined space with a limited but exquisite cast), it certainly has the pulling power. The sumptuous setting of the elite railway carriages, the time-of-the-essence allure and suspense, the crime-of-the-century backstory are all there, but despite all this, even despite Finney’s fastidious timing, the story is rushed. In all, by rights, it should be a better film.

Orient Express was one of Christie’s most impressive novels: rich in character, plot (based on the Lindbergh kidnapping) structured painstakingly with nary a loose end and with a twist not even the most ardent Poirot fan would have seen coming. Where most of her works fit very comfortably into a 90-minute running time (with ample room left for jokes), this deserves – requires – a longer, slower burn. Less a whodunit than a whodidn’t, the book is dense, complex and involved; trying to fit such a story into two hours of screen time is simply asking too much. Barely have we met a character before he or she has blabbed their slice of the puzzle and is ushered out peremptorily to make way for the next.

It feels a dreadful waste of such talent to hurry them so, but even more frustrating is the resulting dearth of characterisation; a powerful, interesting and charismatic dramatis personae is reduced to bare-bones portraits and caricatures. The joy of a Christie plot is in the detail, and we barely have time to process the significance of a monogrammed handkerchief, a grease-spotted passport, a charred memorandum, before the next clue is shoved brusquely before us. In each scene emotions build too quickly to be plausible, Poirot’s insights begin to look like ESP and before we know it everyone is gathered in the observation car for a “wait-what?” explanation and denouement.

It feels a dreadful waste of such talent to hurry them so, but even more frustrating is the resulting dearth of characterisation; a powerful, interesting and charismatic dramatis personae is reduced to bare-bones portraits and caricatures. The joy of a Christie plot is in the detail, and we barely have time to process the significance of a monogrammed handkerchief, a grease-spotted passport, a charred memorandum, before the next clue is shoved brusquely before us. In each scene emotions build too quickly to be plausible, Poirot’s insights begin to look like ESP and before we know it everyone is gathered in the observation car for a “wait-what?” explanation and denouement.

A fine way to spend a wet afternoon, no doubt, but an even better way would be to read the book itself, spread out between cups of tea, with frequent breathers to contemplate hankies, travel documents and the like, before proceeding.

A fine way to spend a wet afternoon, no doubt, but an even better way would be to read the book itself, spread out between cups of tea, with frequent breathers to contemplate hankies, travel documents and the like, before proceeding.

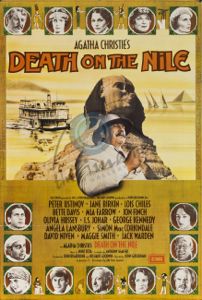

Next is Death On the Nile (1978), the indisputable jewel of the trio. Lacking the polish of Orient Express, it sets the bar a good deal lower but clears it neatly, repeatedly and gleefully. It is directed by John Guillermin, who made The Towering Inferno, and he brings to the film an action-nurtured sense of timing, intrigue and above all, pacing. At a hefty 140 minutes, the film never lags – languid and indulgent when it needs to be, breathlessly fleet just when required, and complemented throughout by Nino Rota’s magnificent, booming score.

Next is Death On the Nile (1978), the indisputable jewel of the trio. Lacking the polish of Orient Express, it sets the bar a good deal lower but clears it neatly, repeatedly and gleefully. It is directed by John Guillermin, who made The Towering Inferno, and he brings to the film an action-nurtured sense of timing, intrigue and above all, pacing. At a hefty 140 minutes, the film never lags – languid and indulgent when it needs to be, breathlessly fleet just when required, and complemented throughout by Nino Rota’s magnificent, booming score.

This pace is amply supported by Anthony Shaffer’s flawless screenplay. Awash with quotable barbs, howlers, asides and occasional actual dialogue, the script fills out almost everyone into a fully-fleshed character and brings the absurdity of the milieu into bold, colourful relief.

Although less serious than Orient Express, Nile has an even better cast: Bette Davis, David Niven, Maggie Smith, Olivia Hussey, Jon Finch, Jane Birkin, Angela Lansbury, Mia Farrow, Jack Warden, George Kennedy… And it truly is glorious; the sort of movie one would rewind of a wet Sunday afternoon and watch all over again.

Murder on the Orient Express features no relationships at all, bar the romance between Connery and Redgrave; Death on the Nile is positively teeming with them. Bette Davis is Mrs Van Schuyler, a wealthy and entitled widow who takes excessive, sadistic delight in tormenting Bowers (Maggie Smith), her paid companion, a woman of good breeding brought low by family bankruptcy. The barely-suppressed vitriol between the two could peel paint. Rosalie Otterbourne, the only thing standing between her alcoholic, hedonistic writer mother (Angela Lansbury) and bankrupt insanity, is courted by a posh Marxist (Jon Finch) who clearly adores her but nevertheless feels the need to lecture her endlessly about the plight of the dispossessed (while inexplicably on a very expensive package tour in Egypt). Plain Jackie (Mia Farrow, producing a very passable English accent) is stalking her former fiancé Simon (Simon McCorkindale) and the ex-best friend (Lois Chiles) for whom he jilted her.

Murder on the Orient Express features no relationships at all, bar the romance between Connery and Redgrave; Death on the Nile is positively teeming with them. Bette Davis is Mrs Van Schuyler, a wealthy and entitled widow who takes excessive, sadistic delight in tormenting Bowers (Maggie Smith), her paid companion, a woman of good breeding brought low by family bankruptcy. The barely-suppressed vitriol between the two could peel paint. Rosalie Otterbourne, the only thing standing between her alcoholic, hedonistic writer mother (Angela Lansbury) and bankrupt insanity, is courted by a posh Marxist (Jon Finch) who clearly adores her but nevertheless feels the need to lecture her endlessly about the plight of the dispossessed (while inexplicably on a very expensive package tour in Egypt). Plain Jackie (Mia Farrow, producing a very passable English accent) is stalking her former fiancé Simon (Simon McCorkindale) and the ex-best friend (Lois Chiles) for whom he jilted her.

David Niven’s Colonel Race makes a charismatic sidekick, but the true treat of the film is of course Ustinov. From Austin Trevor in the 1930s via Finney to Suchet and even including Alfred Molina’s game attempt in the unfortunate update of Orient Express in the early noughties, the focus in filmic interpretations of Poirot has been quite emphatically on his appearance – more so even than on Sherlock Holmes. Physically, Ustinov is wrong in so many ways. He is too tall, too portly. His flyaway hair threatens to do just that at any second. His moustaches grow limp too quickly. His clothing borders on garish at times; he chooses to make himself a figure of fun rather than preserving his fragile dignity at all times…

David Niven’s Colonel Race makes a charismatic sidekick, but the true treat of the film is of course Ustinov. From Austin Trevor in the 1930s via Finney to Suchet and even including Alfred Molina’s game attempt in the unfortunate update of Orient Express in the early noughties, the focus in filmic interpretations of Poirot has been quite emphatically on his appearance – more so even than on Sherlock Holmes. Physically, Ustinov is wrong in so many ways. He is too tall, too portly. His flyaway hair threatens to do just that at any second. His moustaches grow limp too quickly. His clothing borders on garish at times; he chooses to make himself a figure of fun rather than preserving his fragile dignity at all times…

Yet he embodies Poirot’s duality of character better than any other actor. Christie famously loathed Poirot, and regretted having created him shortly after The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in 1920. Her chagrin stemmed partly from the fact that she had created him Belgian, a culture and language of which she knew relatively little, and so was constantly being corrected by readers on the minutiae she had missed. More than that, however, what bothered her most was his popularity – and thus the fact that, if she wished to continue as successfully she had begun, she would have to keep him going. What Christie realised in time was that it was not the verisimilitude of Poirot’s Belgian-ness that made him so wildly appealing, but his manner and his mannerisms: that little head-tilt, his deliberately playing the outsider in order to lull his adversaries into false comfort and thus divulge their secrets as they never would to someone they considered their equal – his insistence on solitude to let the little grey cells do their work. It is these qualities that Ustinov gets absolutely right. So his hair isn’t black, he isn’t the diminutive upstart of the text – so what? He portrays perfectly the character’s quality of being a willing figure of fun so that he might disarm those from whom he is eliciting information.

Yet he embodies Poirot’s duality of character better than any other actor. Christie famously loathed Poirot, and regretted having created him shortly after The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published in 1920. Her chagrin stemmed partly from the fact that she had created him Belgian, a culture and language of which she knew relatively little, and so was constantly being corrected by readers on the minutiae she had missed. More than that, however, what bothered her most was his popularity – and thus the fact that, if she wished to continue as successfully she had begun, she would have to keep him going. What Christie realised in time was that it was not the verisimilitude of Poirot’s Belgian-ness that made him so wildly appealing, but his manner and his mannerisms: that little head-tilt, his deliberately playing the outsider in order to lull his adversaries into false comfort and thus divulge their secrets as they never would to someone they considered their equal – his insistence on solitude to let the little grey cells do their work. It is these qualities that Ustinov gets absolutely right. So his hair isn’t black, he isn’t the diminutive upstart of the text – so what? He portrays perfectly the character’s quality of being a willing figure of fun so that he might disarm those from whom he is eliciting information.

Last we come to Evil Under the Sun. This is the “transitional” film, the lower-budget interstitial between Nile’s casting splurge and the made-for-TV mediocrities that would follow (Murder in Three Acts, Dead Man’s Folly, Thirteen at Dinner, etc), and which not even the likes of Bacall (again), Tony Curtis or Faye Dunaway could enliven. It has the feel of a class reunion, coming four years after Death on the Nile, although in truth the only returning alumni are Ustinov, Maggie Smith and Jane Birkin. Another Shaffer screenplay brings sparkles to what really doesn’t deserve to be so enjoyable a film. Guy Hamilton does a workmanlike job as director – adequate, but hardly exciting.

Last we come to Evil Under the Sun. This is the “transitional” film, the lower-budget interstitial between Nile’s casting splurge and the made-for-TV mediocrities that would follow (Murder in Three Acts, Dead Man’s Folly, Thirteen at Dinner, etc), and which not even the likes of Bacall (again), Tony Curtis or Faye Dunaway could enliven. It has the feel of a class reunion, coming four years after Death on the Nile, although in truth the only returning alumni are Ustinov, Maggie Smith and Jane Birkin. Another Shaffer screenplay brings sparkles to what really doesn’t deserve to be so enjoyable a film. Guy Hamilton does a workmanlike job as director – adequate, but hardly exciting.

It is one of Christie’s lesser works, to be sure – the novel a dull domestic story set in a coastal spa-hotel, the characters listless and the action uninspired. But transplant the action to an anonymous Costa del Sol island, sex up the characters a bit and it turns out that the plot, after all, is plenty intriguing.

The decision to use Cole Porter’s music – instrumental, mostly, in place of a conventional score – is inspired (although likely budgetary). The jauntiness of standards such as “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” and “Begin the Beguine” provides a strict counterpoint to a particularly grisly and coldblooded murder – that of the ageing star and professional dilettante Arlena Marshall, played with grand-guignol gusto by Diana Rigg.

The decision to use Cole Porter’s music – instrumental, mostly, in place of a conventional score – is inspired (although likely budgetary). The jauntiness of standards such as “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” and “Begin the Beguine” provides a strict counterpoint to a particularly grisly and coldblooded murder – that of the ageing star and professional dilettante Arlena Marshall, played with grand-guignol gusto by Diana Rigg.

Arlena’s bitchy rivalry with the hotel’s owner, equally fading showgirl Daphne Castle (a brassy, venomous and irresistible Maggie Smith) provides much of the film’s delicious Baby-Jane-lite acid comedy – in particular a performance of Porter’s “You’re the Top”, each attempting ruthlessly to upstage the other.

Arlena’s bitchy rivalry with the hotel’s owner, equally fading showgirl Daphne Castle (a brassy, venomous and irresistible Maggie Smith) provides much of the film’s delicious Baby-Jane-lite acid comedy – in particular a performance of Porter’s “You’re the Top”, each attempting ruthlessly to upstage the other.

The rest of the cast feels, by comparison, somewhat underused: James Mason as the henpecked husband of Sylvia Miles misses out on much of anything to do; Jane Birkin simpers and is pale, while Roddy McDowall spends most of his time harrumphing and throwing up his hands in camp disbelief as the tell-tale biographer just dying to cash in on his tenuous relationship with stardom.

Nevertheless, between them Smith and Ustinov more than carry the film, their dialogue a delight and comic timing impeccable.

Overall, then 3/5 stars go to Murder On the Orient Express, 4/5 to Evil Under the Sun and a resounding 5/5 to the brilliant Death on the Nile.

*Is it just us or does Agatha Christie’s Poirot seem to be broadcast on hard rotation 24 hours a day, on a scheduling par with old episodes of Friends