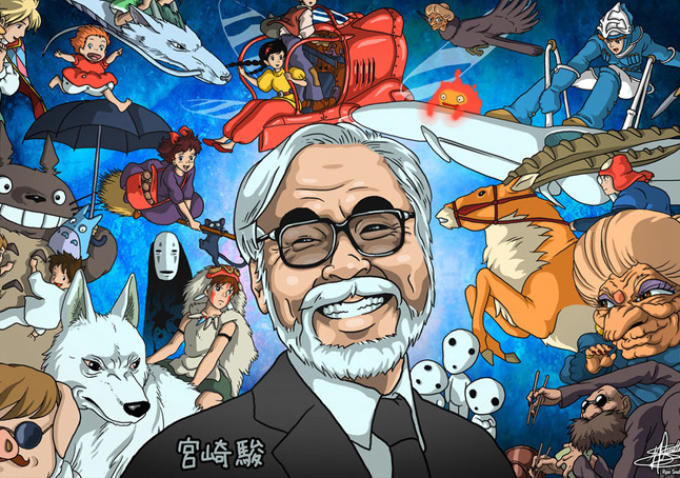

Hayao Miyazaki is the greatest animator ever, and probably the greatest director ever.

Hayao Miyazaki is the greatest animator ever, and probably the greatest director ever.

It’s tempting to leave a review of this monumental boxset at that, and let the controversy of that statement sink in. That phrase alone is almost enough to describe the brilliance of the man celebrated in this collection of his eleven films, a canon small enough to ensure that there is not a single stinker in there. Every single one of them ranges from good, to great, to (more often) sublime. Yet words like ‘greatest’ don’t mean that much, especially when this writer hasn’t seen nearly enough work by other legendary film makers to even begin to make such a definitive statement. Whatever superlatives used, there is no doubt that Hayao Miyazaki is an artist, a visionary and a man of astonishing talent.

This boxset contains 11 films, from the high-octane debut Castle of Cagliostro to its polar opposite, the meditative bio-poetic-pic The Wind Rises, his last film, and everything in between. This includes the legendary Spirited Away, the underseen Kiki’s Delivery Service and one of the greatest films of all time My Neighbour Totoro. There it is again, that word ‘greatest,’ one that is increasingly hard to ignore.

Perhaps it is best to start, when working out exactly why writers are prone to use such words, with the thing that is Miyazaki’s most obvious gift, and that is the power of his animation. Whether it is in intimacy of two young children eating dinner in Ponyo, or in the roaring great waves characterised as living creatures in the same film, Miyazaki’s gift is in helping you see the world in a new way. It’s one of the joys of animation as a medium; a director is only constrained by their imagination, and Miyazaki has zeppelins full of it. Every film is beautifully detailed and bursting with life, and while the pace and size may change – Princess Mononoke is a sprawling, violent epic while Totorois a quiet film full of joy – each one of them is characterised by beauty and invention in equal measure.

Equally remarkable is the way that Miyazaki can craft such compelling stories without resorting to clearly defined villains, and often removing conflict from his narratives altogether. Howl’s Moving Castle and The Wind Rises both clearly show a revulsion to war, although it is never quite as explicit as in the films of his colleague Isao Takahata, but this desire for peace and balance goes further than pacifism on a broad political scale; Miyazaki’s peace is ingrained in the very nature of his stories. In Laputa, Nausicaa, Mononoke and Ponyo, the conflict is with nature itself, but a peaceful resolution is achievable in every single one of them, often with nature triumphing. In Kiki’s Delivery Service, My Neighbour Totoro, and Spirited Away, there is no binary conflict at all, where the story lies in simply observing the characters, with a magical element thrown in to spice things up. This clash of the magical and the mundane is precisely the appeal of Miyazaki. His are films that champion the imagination of the everyday, revealing the mysterious beauty that hides beneath tree trunks and round street corners.

There are many other things to celebrate about the man’s work: his fruitful collaboration with composer Joe Hisaishi; the strength of the female leads in his films; the wry sense of humour that runs throughout; his appreciation of old people; the fact that no two stories of his are the same. But to talk about the brilliance of Miyazaki could take a book, and indeed it has in the past. So to leave it on a personal note, then, it may not make sense to call Miyazaki the greatest director ever when there is still so much cinema for me left to see. All I know is that with the journeys he has taken me on with his films, he is certainly the greatest to me.

The Miyazaki boxset is out on Dec 8th